Catherine Pilgrim: Mrs Larritt in Upside Down Country

Jacqueline Millner examines Catherine Pilgrim’s new exhibition, Mrs Larritt in Upside Down Country.

November 16, 2018

In Exhibitions,

Printmaking, Q&A

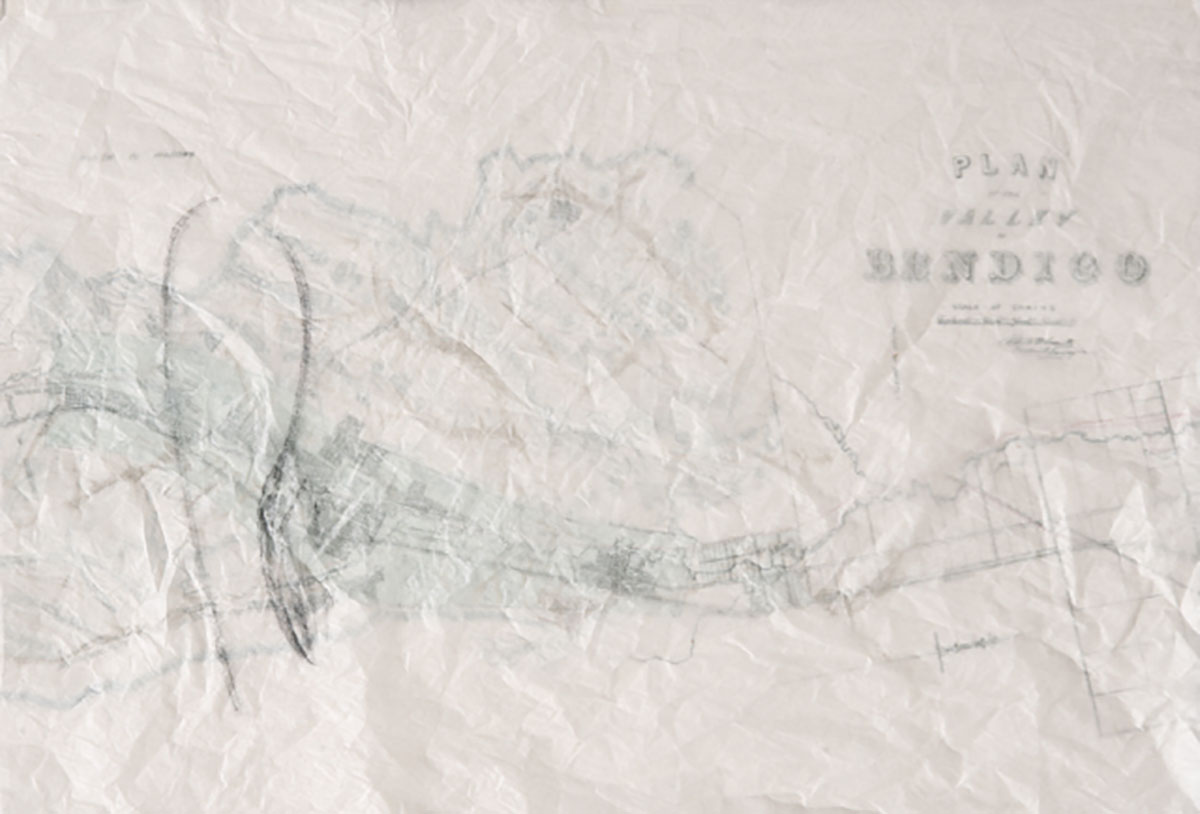

Clockwise from top left:

Bunya1 2018 Coloured pencil with watercolour

Untitled (Chocolate lily and Map) 2018, digital print from lithograph and historic map (SLV) on cushion

Untitled (Murnong with Map) 2018 Stone lithograph layered with reproduction historic map by Richard Larritt (SLV)

Untitled (Chocolate Lily) 2018 Stone lithograph on multiple sheets Silk Gampi, edition of 7

Drawing is at the heart of Catherine Pilgrim’s practice. Beyond a commitment to the rigorous tradition of observational drawing, Pilgrim holds that drawing has an ethical dimension, one of particular relevance in the digital image-saturated world we currently inhabit. The ethics of drawing are bound up with time and attentiveness, but also with the bodily materiality and personal nature of the process. Drawing does not just produce a ‘singular’ or ‘unique’ representation in contrast to a digital throwaway. It attests to the artist’s presence over time, to the (usually private) thinking that may have occurred during that dedicated focus on the subject, to the dynamics between bodily gesture and thought that often open out to new imaginings. Drawing may be a way of caring for the subject, of deigning the everyday with a moment of significance, of tending to the overlooked while at the same time mobilizing the capacity to see things differently.

Pilgrim often uses drawing precisely in this way to generate new understandings of the histories that surround her. In this exhibition, Pilgrim has trained her attention on the history of Bendigo, hoping to complicate and unsettle some of the received ideas that tend to rely on official public records and discount private experience as much as oral testimony and indigenous knowledges. This tendency has been vigorously questioned in recent decades with the rise of feminist, indigenous and social history approaches, which place far more emphasis on the lives of everyday people as well as on biography and personal anecdote. It’s a shift in emphasis that has also increasingly allowed artists a voice in historical debates and discourses: we see this in the role many indigenous artists play in foregrounding alternative histories which challenge the colonial legitimation of massacre and dispossession. But non-indigenous artists also have contributed to re-readings of colonial histories, with now an established strain of critical practice grounded in artistic interventions in historic houses, such as Dudley House, one of the earliest and the most intact government buildings surviving in Bendigo from the early gold-rush era.

What is unique about Pilgrim’s intervention is its reliance on the ethics of drawing to bring together her many points of inquiry: gendered experience in the city’s early days, indigenous legacies, the distinction between public works and domestic lives and between burgeoning urban and declining natural landscapes, and the disavowed practices of caring — for country, for family — that underpin human endeavor. Engaging with Dudley House as a specific site, Pilgrim has coaxed out its multiple histories, meanings and contemporary resonances through a series of works that include pencil drawings, lithographs and objects, installed to evoke the building’s original domestic uses. Her images challenge the structured vision of the ‘historically significant’ male householder— the government surveyor responsible for Bendigo’s city grid — by reminding us of what Richard Larritt’s colonial business relied on, but disavowed: indigenous expropriation and knowledges, and the care of home and body by his young wife, Maggie. Pilgrim’s images merge the abstract geometry imposed by colonizing vision, such as maps and single point perspective, with painstaking depictions of local wildflowers that speak of continuity and resistance over deep time. They monumentalize the native plants of the region — including the chocolate lily and murnong — in the colour most associated with European vision: blue was without a name in many indigenous languages, the colour of willow ware, the English graphic style synonymous with orientalist discourses.

Pilgrim’s drawings are the product of sustained physical endurance, in parallel to what might have been the work of both the surveyor and his wife, as she attempted to raise a family and run a household in a very challenging environment. But with her focus on the unchanging nature of native plants as a constant accompanying these European actors, Pilgrim introduces another, monumental, dimension of indigenous time and human action. By foregrounding care — for home and family, for environment and the everyday objects that surround us — Pilgrim complicates polarized views of history that reduce human actors to pawns serving ideological purposes. Her work prompts us to see the relationality of historical actors. It does not only seek to insert the suppressed experiences of indigenous peoples and women into the historical narrative of her own local environment. Rather it seeks to stimulate our imaginations and material sensations into changing that narrative, to potentially uncover a more complex picture of how history is made, and thereby a much more dynamic relationship between ‘history’ and our contemporary realities.

—

Jacqueline Millner is Associate Professor of Visual Arts, La Trobe University, Bendigo.

This project was supported through a Creative Victoria 2018 Regional Centre for Culture, Local Makers Grant

—

Mrs Larritt in Upside Down Country is at DUDLEY HOUSE, 60 View Street

Bendigo, until 25 November. Exhibition Opening 5-7 Saturday 17th November 2018. Artist talk 24 November, 2pm