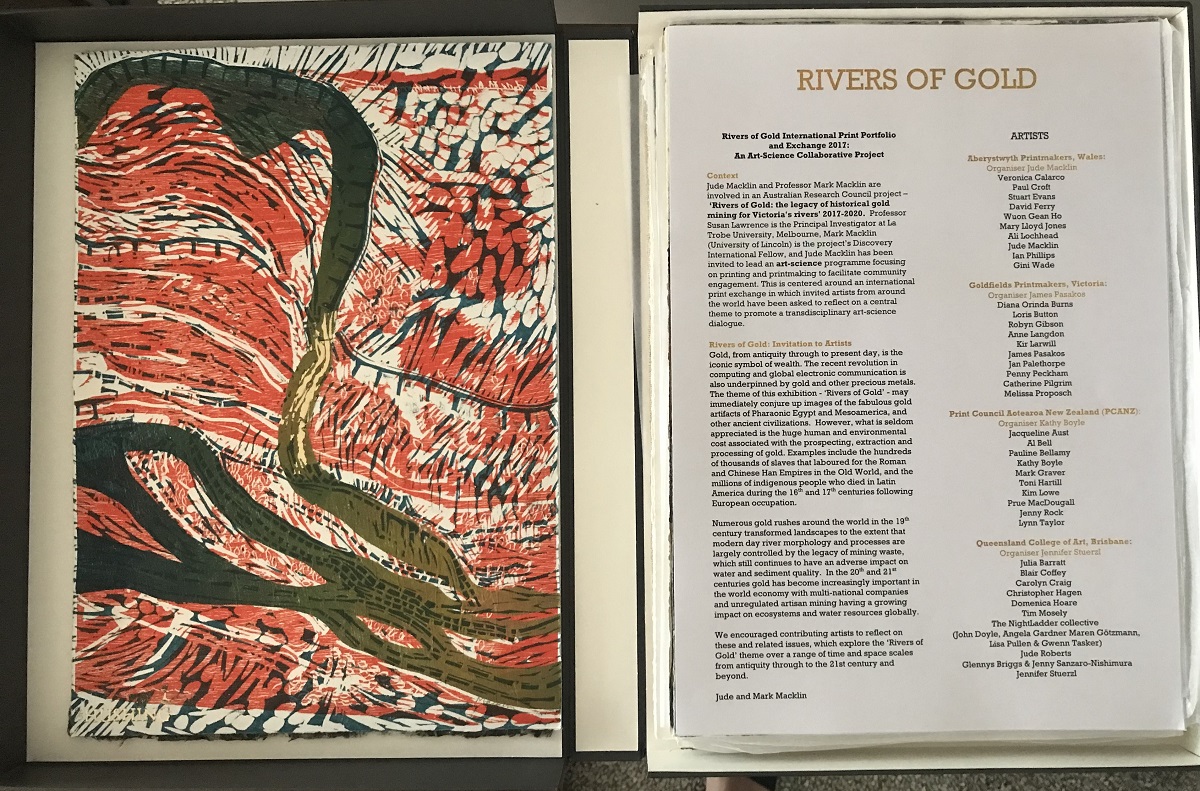

Rivers of Gold

By Jennifer Stuerzl, Jude Macklin, Mark Macklin and Susan Lawrence.

November 16, 2018

In Exhibitions,

Printmaking, Q&A

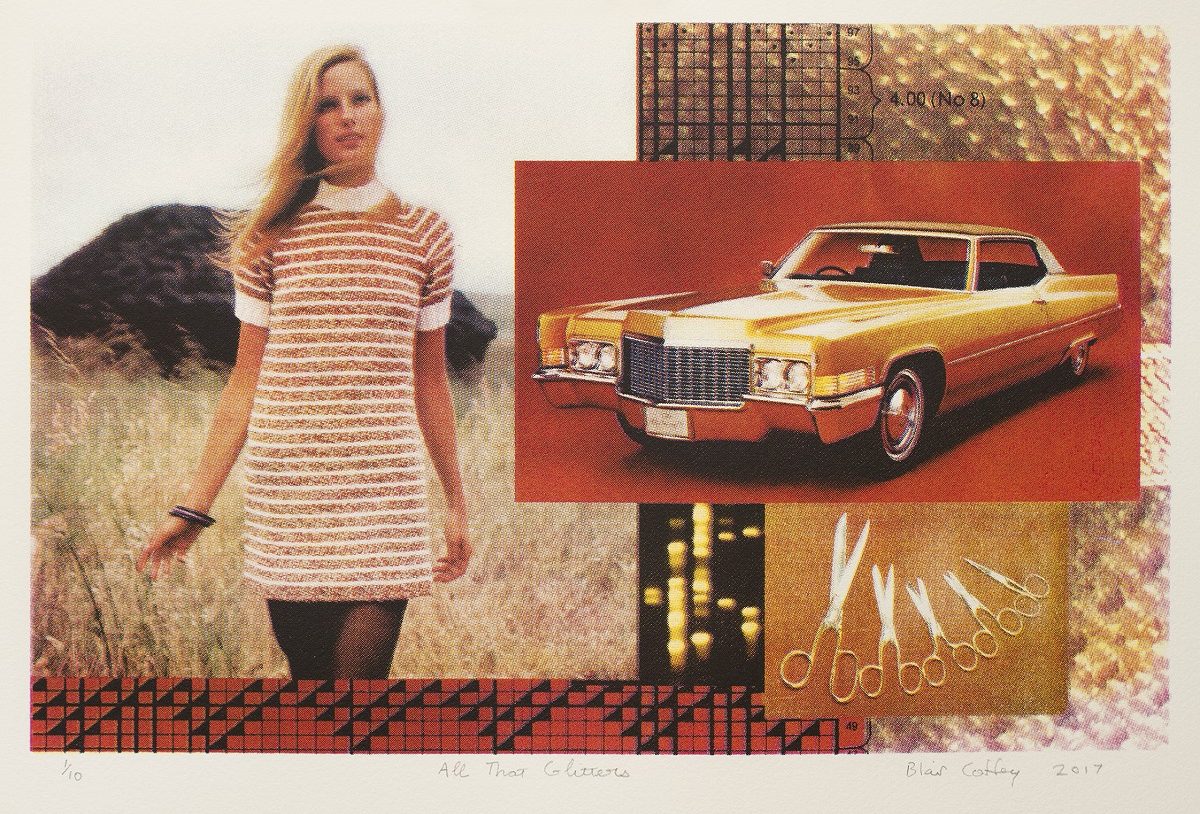

Top: Blair Coffey, All That Glitters, screenprint on Hahnemuhle

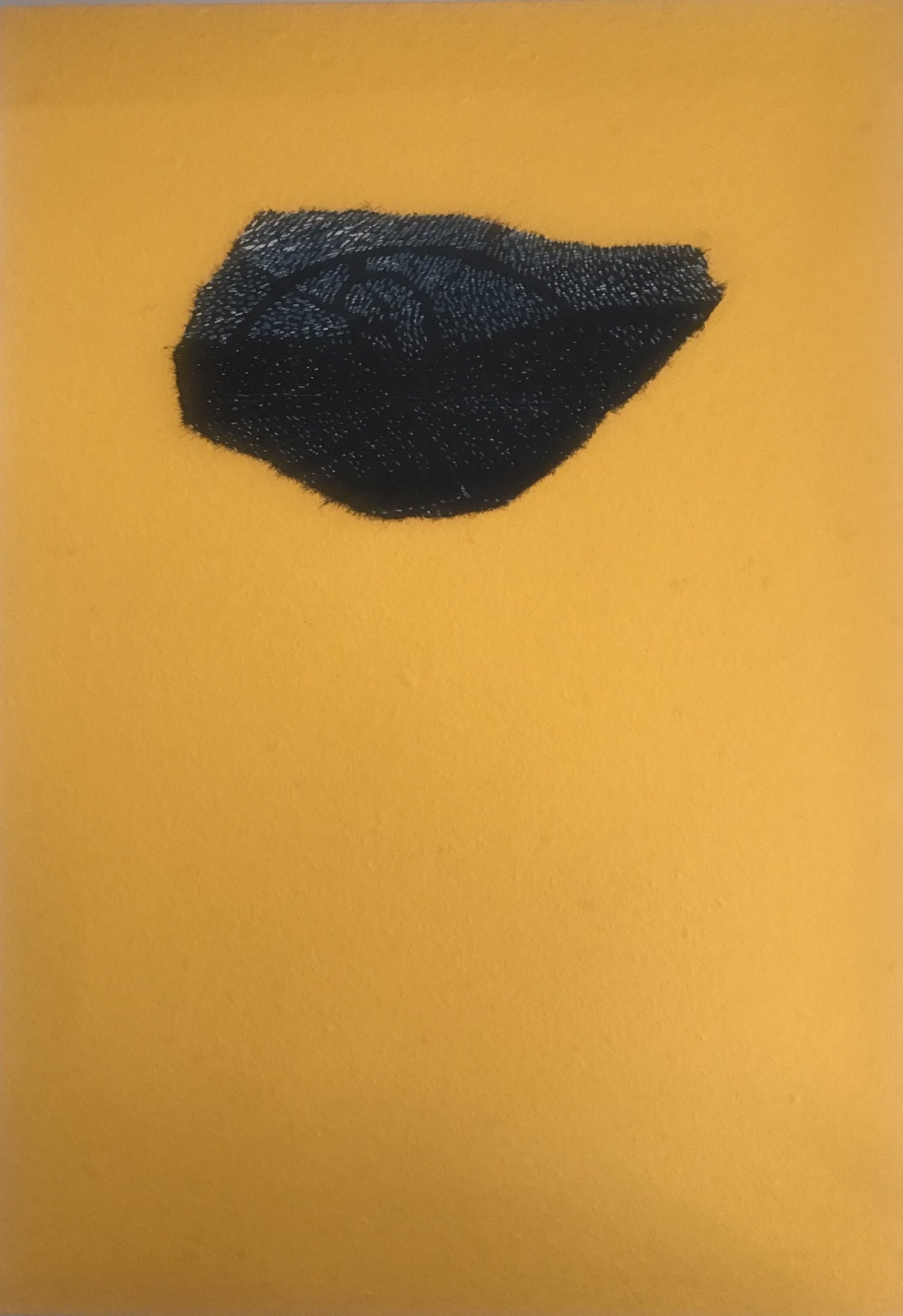

Jennifer Stuerzl, Deluge, 2017, etching on salvaged aluminium, Chine Colle, pigment and gold leaf

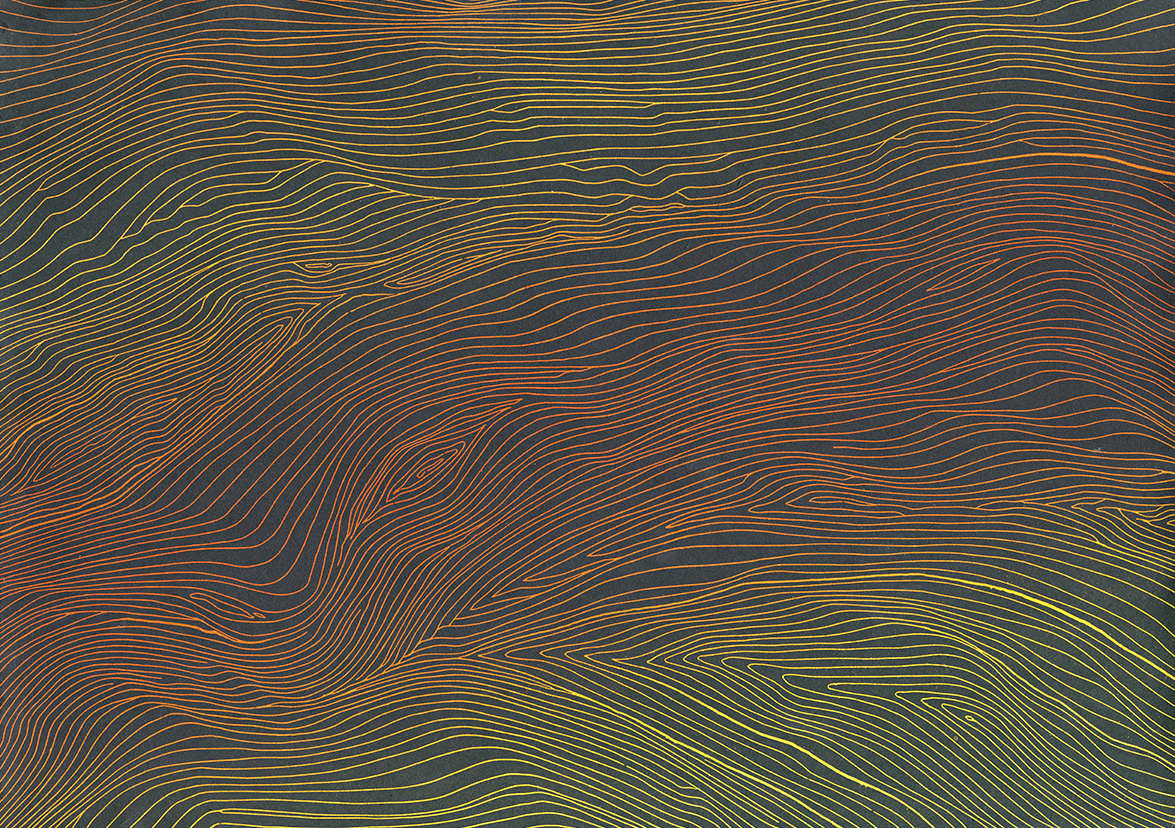

Tim Mosley, Untitled, relief prints, rainforest plywood and linocut on hand made paper

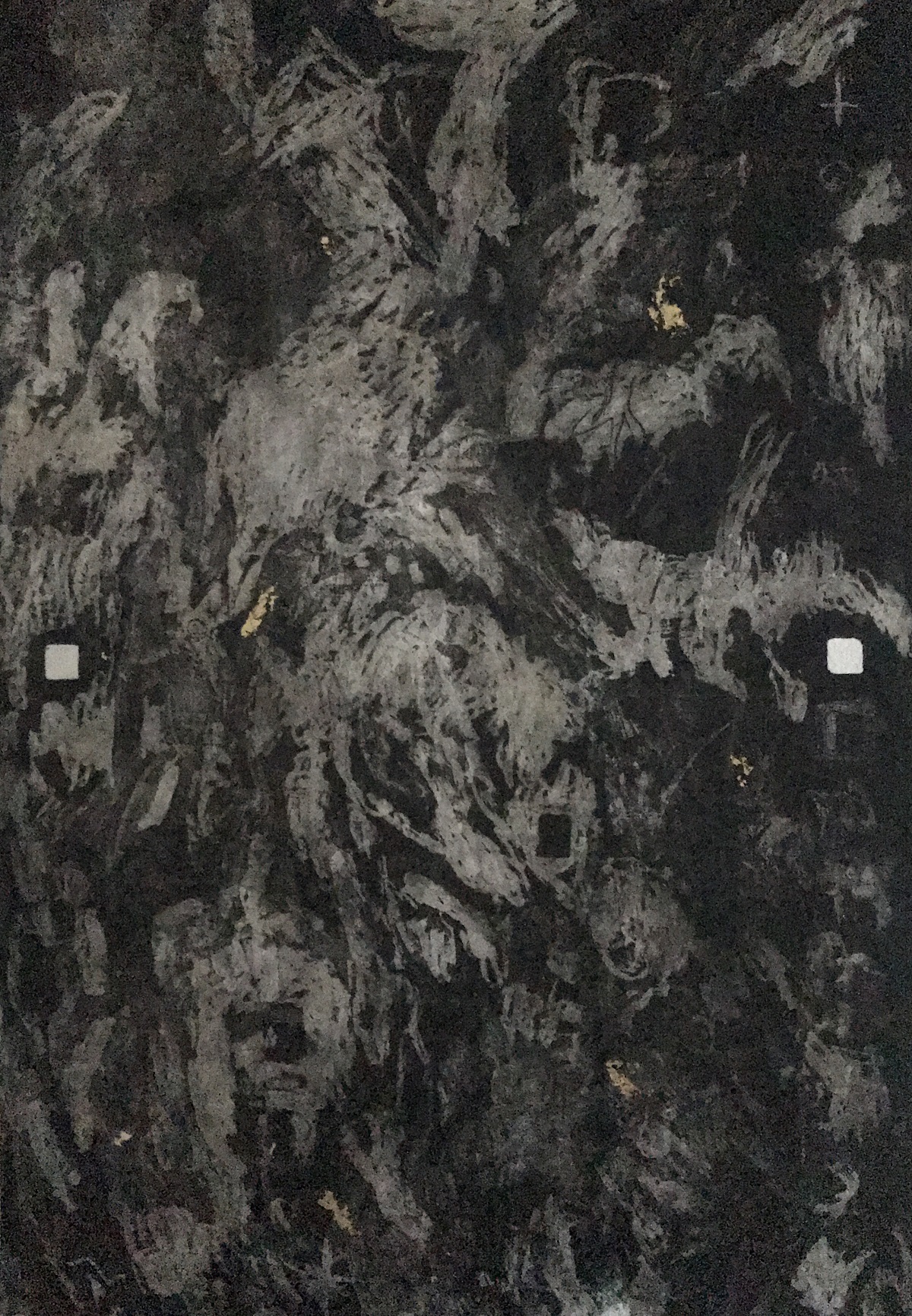

Christopher Hagen, Here-Inhered, monotype and relief etching on Fabriano Rosapina

Jude Macklin, Rivers of gold portfolio Hushing, woodblock, Chine colle and applied gold leaf

Rivers of Gold

International Print Portfolio and Exchange

An Art Science Collaborative Project

Rivers of Gold is a vibrant and varied series of prints that are informed by an amazing story about how significantly fluvial gold mining has changed the world’s landscape. Most of us today have had no idea about how riverscapes and landscapes have been altered by the search for that elusive wonder – gold. But new research is beginning to tell us the story.

An International art-science collaborative of the same name has been informed by new scientific studies here in Australia led by Professor Susan Lawrence of Latrobe University working collaboratively with scientist Professor Mark Macklin, University of Lincoln UK. As might be expected, the artistic collaboration, involving 40 artists from Australia, Wales and New Zealand has expanded the horizons and explored many different aspects of the far-reaching effects of gold on the environment, on our society and on our culture, spanning through time. The project was coordinated by Jude Macklin (Aberystwyth, Printmakers Wales) with local organisers James Pasakos (Goldfields Printmakers, Victoria, Australia), Kathy Boyle (Print Council Aotearoa, New Zealand) and Jennifer Stuerzl (Queensland College of Art, Brisbane, Australia).

Some examples of the artists’ interpretation of each of these themes can be used to illustrate the story. Ian Phillips’ two-block linocut Conquista references the cultural impact of mining in the genocidal campaigns of Europeans in South and Central America. He says that, ultimately, this is a print about murder, theft and about financial and cultural appropriation. Referencing a different cultural context but also addressing cultural encounters and tensions in confluent identities is Tim Mosely’s relief print Untitled, using rainforest plywood and linocut on handmade paper. Mosely says that the “The rainforests of the Sa:mba:leke, akin to a river of gold, are a resource exploited by my ‘home’ culture at the expense of the culture of my formative years…” The exploitation of Indigenous cultures as a result of mining is investigated in Glynnes Briggs and Jenny Sanzaro-Nishimura’s serigraph print Mining Dja Dja Wurrung and in Jude Roberts’ lithograph Path Ways in which she acknowledges the Indigenous contribution to the success of mining expeditions capitalised upon by prospectors. The displacement of people from their land continue into the present day and their personal stories of loss are part of the goldfield history also expressed in Julie Barratt’s collagraph Cemetery Paddock.

With time, gold ventures continued to prosper with the invention of effective and mechanised mining techniques which consequentially increased the environmental and cultural impacts of the mining.

Historic forms of mining and the effect on the environment are investigated in Jude Macklin’s woodcut called Hushing after an ancient form of hydraulic mining used to recover precious metals such as gold and silver. Macklin says it had a devastating impact on the landscape and describes it as a one of humankind’s most significant and land-changing activities through erosion of the bedrock, regolith and soil to created huge gullies and fanlike sediment bodies of mining waste in many upland river catchments.

Environmental damage is also considered in terms of the Australian riverscape in Jennifer Stuerzl’s etching Deluge, which evokes the effect of flooding and habitat destruction a consequence of mining and ecological disturbance to riverine ecology with long-term and continuing effects. Veronica Calarco’s lithographic print What Remains reveals the cut forests of the Australian landscape from memories of her childhood visit to the gold fields of Victoria and Broken Hill, NSW. The image of tree stumps shows explicitly the devastated landscape that occurred along the rivers and streams of gold mining locations of Bendigo, Ballarat, and the cultural displacement of the original custodians of the land. The technological advances of mining that increase productivity but at the same time had consequences on the environment by allowing a vast amount of material to be crushed and the precious metal extracted are portrayed in James Pasakos’ silkscreen print The Garfield Waterwheel. The mining and pollution from the collapse of tailing dams are investigated in several prints: the NightLadder collective’s etching and dry-point Breach; the contamination of rivers and streams with mercury and cyanide waste from gold mining, and the negative effects of this on local communities expressed through colour and texture in Alison Lochhead’s collagraph Dirty Gold – Rivers of Gold. Christopher Hagen’s monotype and relief etching Here Inherited raises questions about the cultural and environmental implications of mining. He says “This work is at first a depiction of where gold is found and where I believe it is better off staying, but the linework flickers between rock strata, topography, rivulets, and the furrows of skin.”

All of these works reference the effect of mining and technological developments upon the riverine environment and social and cultural implications of mining.

Contemporary references to the obsession with gold are addressed in Carolyn Craig’s …. Landscape My Desire, a photopolymer print referencing the “commodity desire of mapping the gold price index for a month is imposed over a blown-up image of a Victorian gold field”. Blair Coffey’s All that Glitters screenprint uses images of golden hair, golden fields and golden objects and references cultural constructions and modern-day datamining through the technological advances of genetical genome sequencing.

From a different view, Domenica Hoare in The Three Greedy Sisters references the Grimm Brothers and tells a moral tale about the desire for gold and the consequences of avarice. Also referencing folk lore is Cathy Boyle’s print of the folksong Bright fine Gold, a song that originated in the Ballarat Australian goldfields and travelled with miners to the New Zealand goldfields indicating how the mining culture was transcultural and frequently involved extreme living conditions that could lead to ill health and death in the goldfields far from the homelands of the prospectors.

The prints encompass a range of print making techniques including but not limited to stone, aluminium and photopolymer plate lithography, aluminium and copper etching, linocut woodblock, serigraphs and solar plates, both separately and in some works in combination with digital prints.

–

An online version of the catalogue can be found at http://www.whitefire-designs.co.uk/rivers_of_gold.pdf