From top:

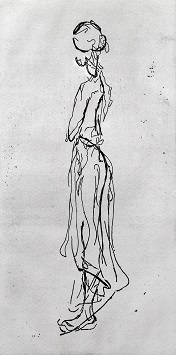

Debra Luccio, Reach (2019), monotype on Velin Arches paper, 60 x 45 cm. The Australian Ballet’s Marcus Morelli rehearsing Tim Harbour’s Filigree and Shadow.

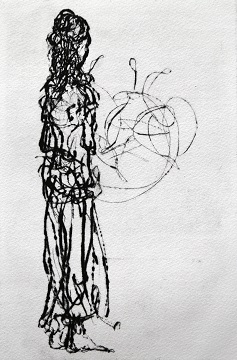

Debra Luccio, Filigree and Shadow (2019), monotype on Velin Arches paper, 60 x 45 cm. The Australian Ballet’s Jade Wood and Jake Mangakahia, rehearsing Tim Harbour’s Filigree and Shadow.

Debra Luccio, Aurum (2019), monotype on Velin Arches paper, 40 x 30 cm. The Australian Ballet’s Sharni Spencer and Christopher Rodgers-Wilson rehearsing Alice Topp’s Aurum.

Debra Luccio, Flying Rose (2018), monotype on Velin Arches paper, 45 x 60 cm. Dimity Azoury, the Australian Ballet, rehearsing Graeme Murphy’s The Silver Rose.

Debra Luccio, Seated Ballerina (2019), drypoint on Velin Arches paper, 25 x 20 cm. Dancer of the Australian Ballet rehearsing Graeme Murphy’s Shéhérazade.

Debra Luccio, Valerie (2019), etching on Velin Arches paper, 25 x 10 cm, edition of 50. The Australian Ballet’s Valerie Tereshchenko rehearsing Graeme Murphy’s Firebird.

Debra Luccio, Alice (2019), drypoint on Velin Arches paper, 25 x 20 cm. Choreographer Alice Topp creating Aurum.

With fifty-two pieces exhibiting at Melbourne’s fortyfivedownstairs gallery this month, Debra Luccio’s next series of prints, Dancing from the Dark, Looking for the Light, shows how her new textures, palettes, and moments of inspiration can dance on paper in delicate clashes of colour and motion.

Summoned in etchings, drypoints and monotypes, the stark ballet dancers in Luccio’s images – born from the careful removal of ink – push through the sweeping backgrounds with tangible momentum, backgrounds much brighter overall than those in her numerous previous collections.

Already an established photographer, painter, and printer, she travelled to New York City in 2007 and discovered an explosive passion for dance in the New York City ballet. Shifting from painting and photographing to monotype, she began her now synonymous relationship with dance, and the ballet.

Drawing inspiration from what the dancers have told her are “the beautiful in-between moments” of their craft, Dancing’s source material consists of three productions presented by the Australian Ballet in the last year: Graeme Murphy’s dedication Murphy, Alice Topp’s award-winning Aurum, and Tim Harbour’s Filigree and Shadow, all in her characteristic style: pointed toes pirouetting on the fringe of abstraction.

What’s your process when putting the dancers on the plate?

DL: From the beginning I know I’m going to rehearsals to make them an exhibition. If I can photograph them I will, but otherwise I’ll do sketches or remember certain colours that strike me, in costumes and in lighting. On the plate I think about where the dancer sits and first bring in skin tone with a roller, dabbing often. Then I start to go a bit crazy and bring in my colours. I look at what’s in my reference picture, and think about being in the dance studio, what really inspired me at the time, the colours I really want to have in my image and the energy surrounding the dancers. Sometimes it’s even the emotion of the dancers that influence the colour; for Aurum the dancers are sometimes really struggling, and I use pressure and my roller to emphasise that. This is all the starting sketch.

From there I use my roller to pull those colours around and start giving the blend some depth. I put paint where I want strength, almost to place weight in the image using the background.

Somewhere amongst this I get my cloth out and start pushing that viscous etching ink around with my finger, quite like finger-painting only backwards, sculpting into the dark; the harder I wipe the lighter it is. These days I’m working with a lot less ink on the plate, making my images lighter overall.

How do you accomplish that blend of colour in the background of your images?

DL: It came out of my curiosity about the thick etching ink, and how it would be with itself in different colours when pressed together, whether it would stay separate when printed, so I just experimented and, well, it worked! By rolling layers of etching ink on top of themselves and then forming my image, all the textures and colours would largely remain as I’d placed them, so I think a lot of the foundation happens there. There’s a lot of chance involved, and a lot of different things could change and be created that I’m not in control of but that’s where the magic comes from, I feel. I think I was really lucky this style suited me.

I have changed it subtly, in that I used to have a lot more darkness, and I think it’s because the performances I’m working with are different too. The first show I did – in NYC – was called LandFall, in which the background was really black, and the dancers were lit up and wearing white. The Queensland Ballet’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream was all dark blues and greens. I think the ink was much thicker on the plate because of that, which put a lot of contrast between the background and the dancers. I think if I did another performance that was made up of dark colours my work would likely come out all dark again.

Can you tell me about one of the pieces in Dancing?

DL: Sometimes when I’m working – and it doesn’t happen all the time – I can mentally get into a zone where I’m not thinking about anything. Maybe it comes from the simplicity of pushing ink with a finger, the inherent childishness of that, but when it happens, I love it. There’s a piece here called Reach with which I had one of those moments while painting the dancer’s chest, a very expansive part. When I realised what was happening after a while, I snapped out of it, and then I struggled like crazy with his face but that’s another thing.

The angles on him were challenging because you can’t see much of some things. I just try to think “don’t think, draw what you see”. It can be hard sometimes, but I must keep that in my head.

Usually I’ll complete a monotype in one day but that’s actually one of the few I covered and worked on the next day. I was exhausted the day I worked on that piece. I loved it, but I was exhausted. The beauty of covering it overnight was, as I pulled it off the plate the next day, it created lines in the top of the artwork that added to the upward movement. It came out organically, different to the marks I could have made with my finger or a brush, and different again to the roller marks.

What’s coming up after Dancing?

DL: I’d love to do some more work with the Australian Ballet because it’s the Artistic Director David McAllister’s last year with them. He’s been in that role for 20 years and he danced for them for around that amount of time again. He’ll go down in history as one of their greatest contributors and I’d love to do more work with him.

—

Dancing from the Dark, Looking for the Light will be at fortyfivedownstairs, 45 Flinders Ln Melbourne, 1-26 October 2019.

www.fortyfivedownstairs.com