Superpowers #4: Ancestral waters

words by Hannah Presley

artwork by Lisa Waup

The Print Council of Australia’s Superpowers project, funded by Creative Victoria, is a writing and printmaking endeavour. This is the final of the four specially commissioned essays and art works in which writers and artists interrogate various forms of energy in the context of the global climate emergency. Words by Hannah Presley, artwork by Lisa Waup.

24 May, 2021

In Exhibitions,

Printmaking, Q&A

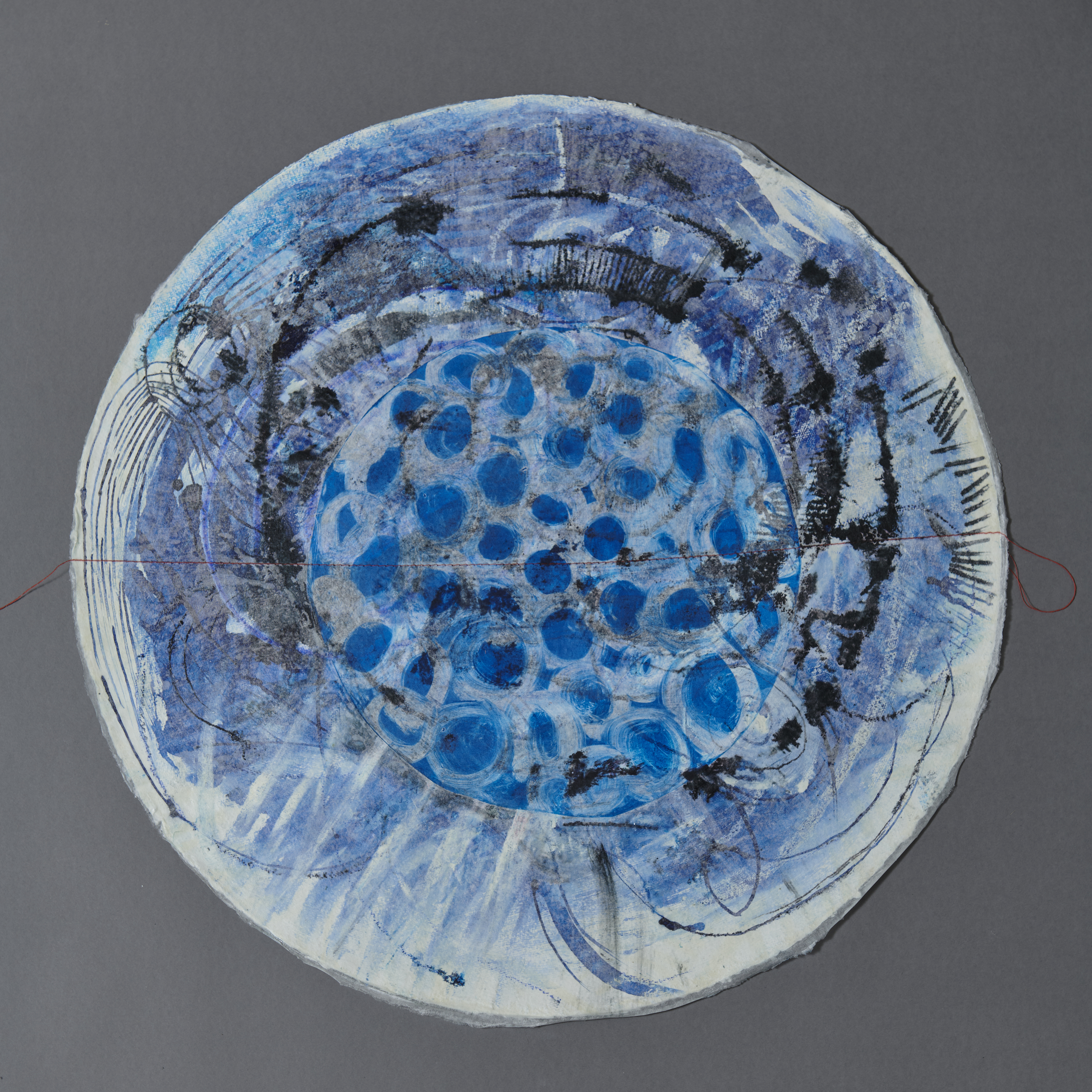

Artwork, from top:

Lisa Waup, Pocketful of Sea Shells,

2020, Khadi cotton paper 320gsm, Japanese

rice paper, enamel paint, intaglio ink, oil pastel,

ink, cotton thread, gel medium, 56 cm diameter

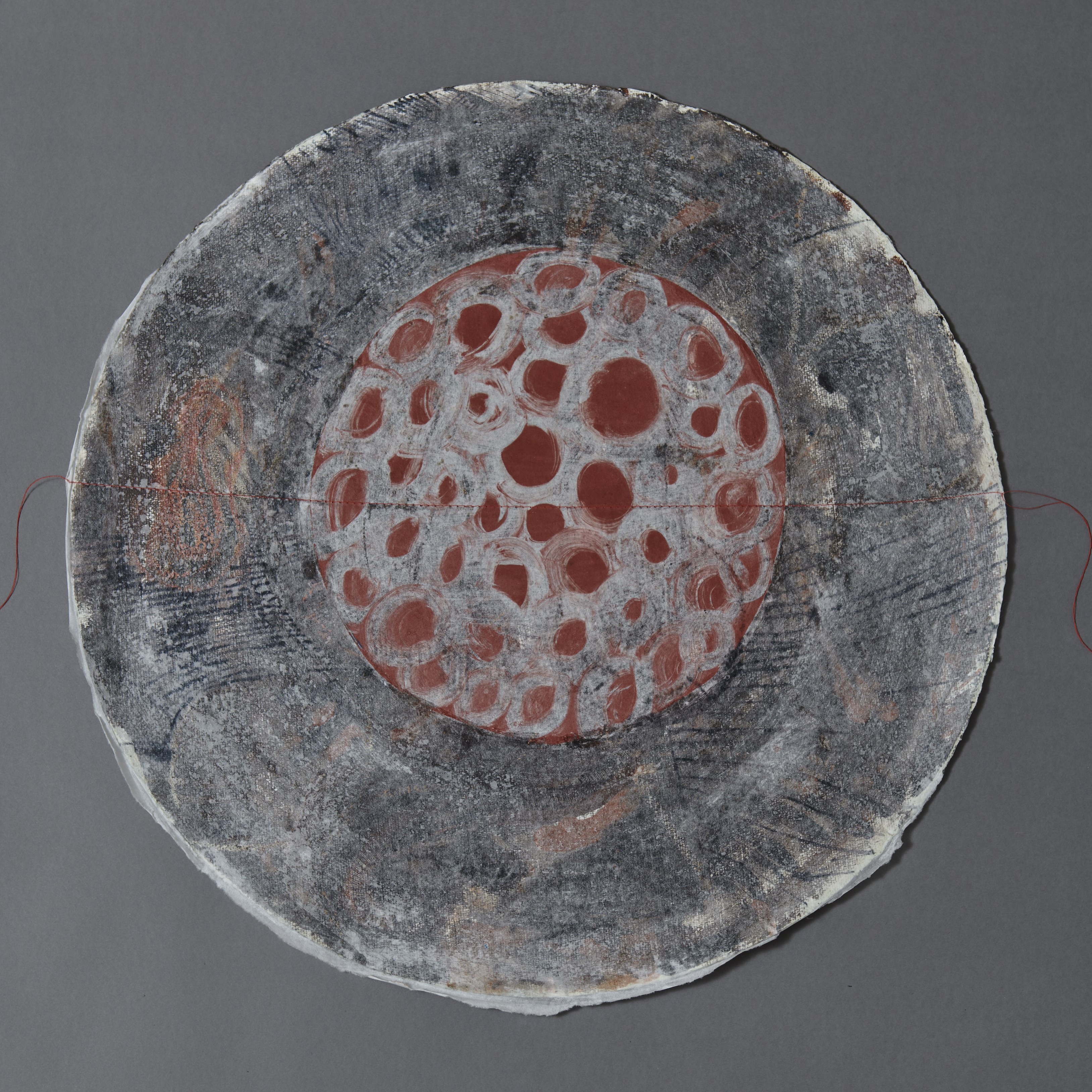

Lisa Waup, Muddy Banks,

2020, Khadi cotton paper 320gsm, Japanese

rice paper, enamel paint, intaglio ink, bitumen,

ochre, binder, oil pastel, ink, gouache, cotton

thread, gel medium, 56 cm diameter

Lisa Waup, Ancient Forest,

2020, Khadi cotton paper 320gsm, Japanese

rice paper, enamel paint, intaglio ink, oil pastel,

ink, gouache, gold leaf, cotton thread, gel

medium, 56 cm diameter

Australian Inc.

I grew up near the Murray River—fresh water, red dirt, paddy melons, fishing, yabbies and pelicans. I can’t remember the first time I saw the ocean, but I remember my dad telling me his first experience. A skinny little blackfella from Alice Springs about twelve years old, a desert rat on a school trip, his first time outside of the landlocked town. I can hear him telling the story, see him shaking his head ‘Han, it was huge!’ dramatic pause… ‘We got down there and we all ran and jumped in the sea, a wave came and bowled us all over and every one of us got out real quick and we was spewing from the salt water and all said that water’s no good! That’s it, I’m not going back in that bastard again, make you sick that water.’

When I think of water, my thoughts go to my family. I see my grandfather surrounded by fishing hooks and my dad throwing the yabbie nets in and catching shrimp for bait with my little sister on the muddy edge of the river. That kind of black mud that squelches between your toes and dries a light grey colour. Swimming has always been my thing, I was always the first one in and the last one out, I have even fallen asleep floating in a body of water out bush that could more accurately be referred to as a big puddle. Being near water holds happy memories for me and my family.

I have always wondered if memories travel in water, stored and saved in our bodies like glossy little droplets of identity. A sense of self stored in the water that contributes to the composition of our brains, our blood and even our bones. Perhaps water is where our ancestors exist, making sure we remember them, sending messages that appear as instinct, rising up with guidance and assurance, alarming us with warnings, akin to intuition, like the ripples from a stone thrown into a lake, a disturbance throughout your entire being.

First Peoples across the country are connected by song and stories of shared creation spirits that are made of water, connected to water and spiritually entwined with water. In the beginning it was water serpents that carved out the land, creating definition with hills and valleys, with water pooling and soaking, winding its way across the dry earth, leaving behind in its wake rivers crashing through blood-red cliff faces, exposing smooth hot rocks. Ancestral spirits still bring the big storms each season, the thunder and lightning that reminds us to not forget our responsibilities to Country.

We all come from water, from energy buzzing around at this early time of creation, fizzing into existence with our kin, the trees, plants and animals. Imagine knowing you were personally connected with the waterways since the beginning of time, knowing that feeling deep inside of connection and deep respect were the actual building blocks of your physical self. Water is life, not just for us, but for every living thing.

Alongside this inheritance comes an obligation to protect our waterways— equally to the land. This is an ongoing fight that has been steadily pursued since invasion. Aboriginal people have battled to overcome intentional actions and policies to sever our ties with the land and waters, challenging our sovereignty and denying our rights to practice culture.

Aboriginal people have a solid history of resistance fighters and ecological warriors, and we have never been passive in regard to our Country. Alongside these cultural leaders we can find the strength to maintain our connections or re-connect with the waterways, which for many is still the heart of our relationship with the land.

Across the south-east of Australia, the Murray River has sustained First Peoples for many generations, providing a vital source of freshwater and food as well as materials for trade and tools. The fertile soils along the banks of the river have sustained magnificent gums including the black box (Eucalyptus largiflorens) and coolabah trees (Eucalyptus coolabah) as well as the impressive river red gums (Eucalyptus camaldulensis) which line the banks along the length of the river.

My grandfather had a magnificent old river red gum on his property, he knew how much I loved it and one day he joked that he had sold it to make matches. I can still feel the sadness I felt in that instant and the relief when I realised he was teasing me.

After such a long history of harmony and health, more recent generations have seen the river inflicted with unrelenting devastation. As farming and agriculture have diverted much of its flow, the resulting erosion and salinity are having a crippling effect on the river and its inhabitants.

One of the most famous long-time inhabitants of the Murray River is the Murray cod (Maccullochella peelii). Once reaching sizes of almost two metres and weights of more than 100kg, these giants of the river were heavily overfished by European settlers and have never recovered. Australia’s largest freshwater fish is now considered critically endangered.

I have always respected the mysterious Murray cod, visiting my grandparents in Wentworth, a small town on the NSW/ Victoria border where the Murray meets the Darling River, there was a small museum that housed a giant living cod in a large fish tank. I remember it being a huge fish, and wonder if it’s still there swimming around. Murray cod can live for more than seventy years.

The diverse and vibrant animal and bird life of the riverlands depend on a healthy river to survive. Changes to water levels, logging and pollution are affecting their habitats and, as a result, we are seeing mass endangerment and loss. The balance is out and it doesn’t seem like we are taking it seriously enough as a nation. We are living in a time where our dingoes are still seen as threats rather than being acknowledged as key to a healthily functioning ecosystem, showing us that farmers are still being prioritised over cultural knowledge of the land.

Traditional Owners are in perpetual mourning as they see species disappear and their homelands poisoned and destroyed. It is hard to reconcile how a foreign understanding of working the land was placed directly over the top of genuine knowledge, smothering a relationship that had been maintained for generations.

It has never been more important to engage First Peoples in the decision making for the future health of our waterways. As the world watches, more extreme weather events are occurring, ocean temperatures are rising and reefs are dying. The cultural impacts of climate change are being felt by First Nations people globally, many communities around the world living with water shortages, polluted water and rising sea levels that threaten to engulf their traditional lands. There is an understandably high level of fear and anxiety about the future for these communities.

In Tasmania, the giant kelp forests have almost vanished, with a staggering ninety-five per cent already lost. The kelp beds have been maintained over generations, harvested as a useful material that among other uses was collected to create water carriers. The giant kelp is the foundation of the Great Southern Reef, which is home to important marine life including weedy sea dragons (Phyllopteryx taeniolatus) and a diverse range of molluscs.

The kelp beds were once home to many different maireener shell species, pearlescent treasures culturally linking Tasmanian First Nations women through time. These exquisite shells, once collected and prepared, are then strung into delicate necklaces, a tradition that has continued unbroken. This extreme loss is directly connected to climate change: as the water temperatures rise the kelp no longer grow and the warmth is in turn affecting the spawning and survival of the shells.

We have reached a turning point where we desperately need to listen to our First Nations communities. The Earth is telling us now is the time and if we ignore it, all will be lost. In this country we are seeing younger Indigenous generations take the lead in voicing climate warnings. They are doing this with the support of their communities and guided by their Elders.

First Nations artists play a vital role in raising awareness of the significance of cultural knowledge, asserting the way culture can expand and adapt, grow and change as we do. Artists also show us how the environment is changing, from weavers seeing the strength of their traditional grasses weaken due to fluctuating water levels, to shell-necklace makers struggling to find shells due to the loss of their underwater habitat.

For Lisa Waup, a Gunditjmara and Torres Strait Islander artist, art-making allows her to give voice to the things that matter to her most. Her art comes from the heart and is a reflection of her understanding of the world around her. Waup’s training as a printmaker has created a strong foundation for her work in a variety of materials, drawing on her confident mark-making and intricate patterns. In the last few years, Waup’s hand-drawn designs have been successfully transferred to fabrics via her collaborative relationship with fashion designer Ingrid Verner. This ongoing project has highlighted Waup’s ability to convey deep meaning through complex line work.

Waup strongly associates water with women, birth and kin, seeing the cyclical nature of water as a reflection of family and spiritual growth. Family is at the centre of Waup’s practice, and her three children are often referenced in various ways throughout her work. Lisa shares,

A circle for me symbolically represents family and details the strength with in family—ongoing and unified. My work details the paths and connections to bloodlines. It shows where I am going and also where I have been, and gathering the strength to do so from my ancestors.

Many First Nations cultures are matriarchal, with women holding cultural knowledge for the wider community, and there is an abundance of respect for women’s role as nurturers, providers and protectors all built into culture. Across the world, women are still carrying water for miles, gathering grasses and weaving fishing nets to feed their children. Waup connects with these universal maternal experiences, linking the nature of water as a ‘force to be reckoned with’, the fierceness she feels being a mother. Waup takes this further again, expressing the complexities that exist with her own mother figures,

I travel in interlocking circles of family, friends and historical findings—journeys of self. My practice has a strong spiritual element. I have an intuitive connection to Country, of the Earth and waterways being a living being. As the details of my history have always been blurred, and there are facts missing, this connection is a replacement for what is unknown. My spiritual connection to Mother Nature becomes a relationship that stands in for this loss of knowledge, and forms the connection to my past without the facts being present.

Water refreshes the lands, replenishing waterholes and rivers, washing the leaves clean and making the rocks stand proud and sparkling. Water is the story of adaption, resilience and survival and connection. Lisa responds,

Connections to the Land and Sea deliver me to a place of belonging and peace. It surrounds me, it nurtures me. It delivers me calm. It inspires me to do what I do as an artist. I can hear the old ones calling me.

I often think of a little frog in Central Australia that has been found in the Finke River, the oldest flowing river in the world. The Spencer’s burrowing frog (platyplectrum spernceri) buries itself in the dry sand of the river beds. This little frog creates a bubble around itself under the sand, where it waits for the water to come, sometimes waiting years. When the big storms start up north and the fat drops of rain start falling in the desert, the little frog comes back to life, as if by magic, challenging what we think we know about water.

All living things are connected by water, First Nations people know this relationship intimately, but we all experience a connection, sometimes simply in the way we are all united in our enjoyment of watching the sun set over a magnificent ocean expanse.

—

Hannah Presley is an Aboriginal curator based in Melbourne, she is currently curator of Indigenous art, National Gallery of Victoria. Presley was the inaugural Yalingwa curator at the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art where she curated A Lightness of Spirit is the Measure of Happiness and was First Nations Assistant Curator for Tracey Moffatt My Horizon at the 57th Venice Biennale. Presley draws on inspiration from her early roles working in Central Australian Art Centres and as Exhibitions Officer at Araluen Galleries, in Alice Springs. Presley has worked in curatorial roles with the Koorie Heritage Trust, Footscray Community Arts Centre and Craft Victoria.

Lisa Waup is a mixed-race First Nations and Italian woman with a multidisciplinary art practice, born in Naarm (Melbourne). Waup’s practice is studio-based, and has a strong connection and symbology through her work and materials which connects her to family, Country, history and story. She works across weaving, printmaking, photography, sculpture, textiles and installation and her work eloquently illustrates her life’s journey through discovery and connection. Waup’s practice highlighting the importance of tracing lost history, ancestral relationships, Country, motherhood and time which ultimately are woven stories of her past, present and future into contemporary forms.

—

The Print Council of Australia’s Superpowers project is supported by the Victorian Government through Creative Victoria.

—

Join the PCA and become a member. You’ll get the fine-art quarterly print magazine Imprint, free promotion of your exhibitions, discounts on art materials and a range of other exclusive benefits.