From top:

Melissa Smith

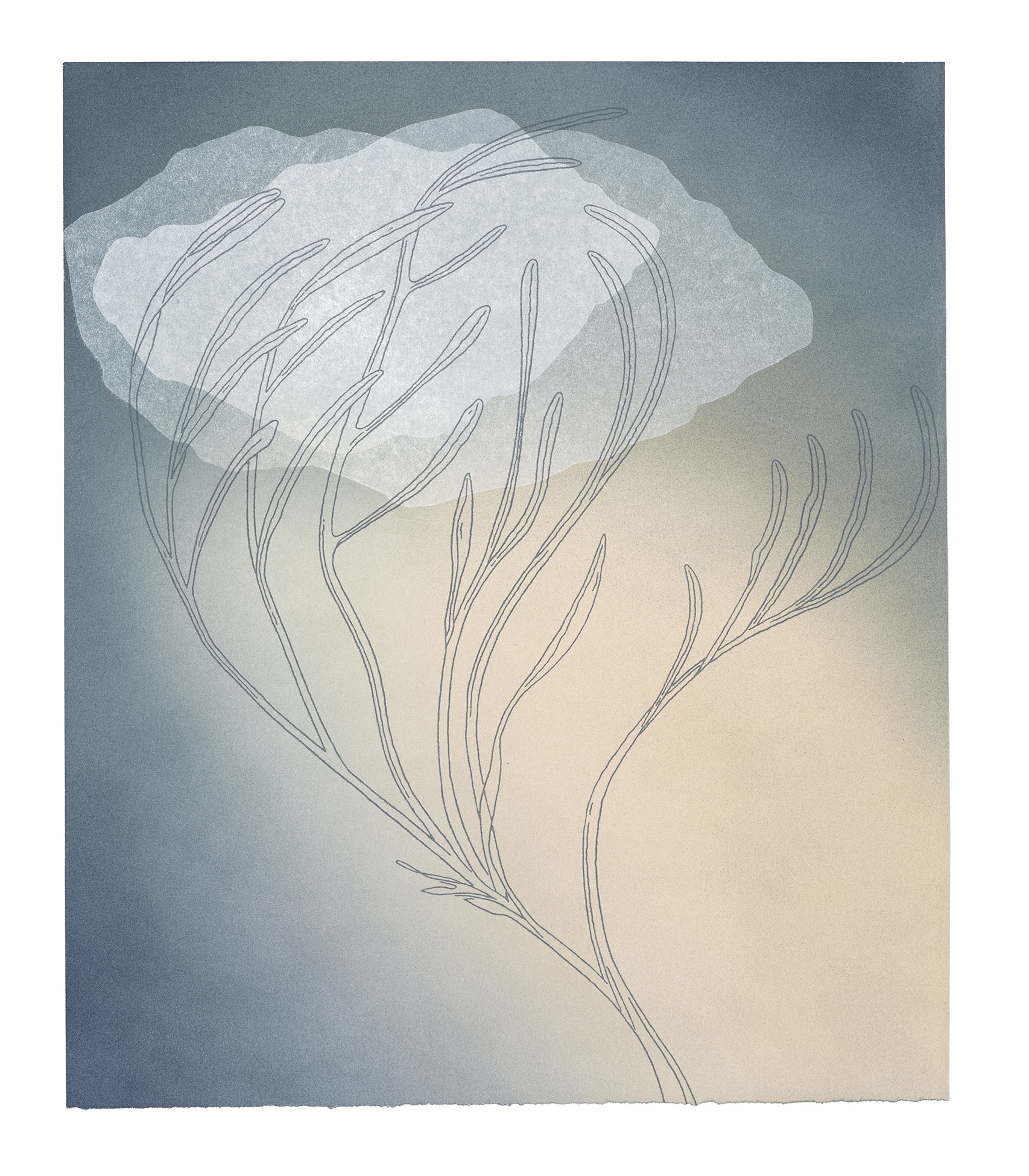

- Listen Deeply – Lake Sorell, 2021, intaglio collagraph, triptych, 76 x 120 cm, edition of 4

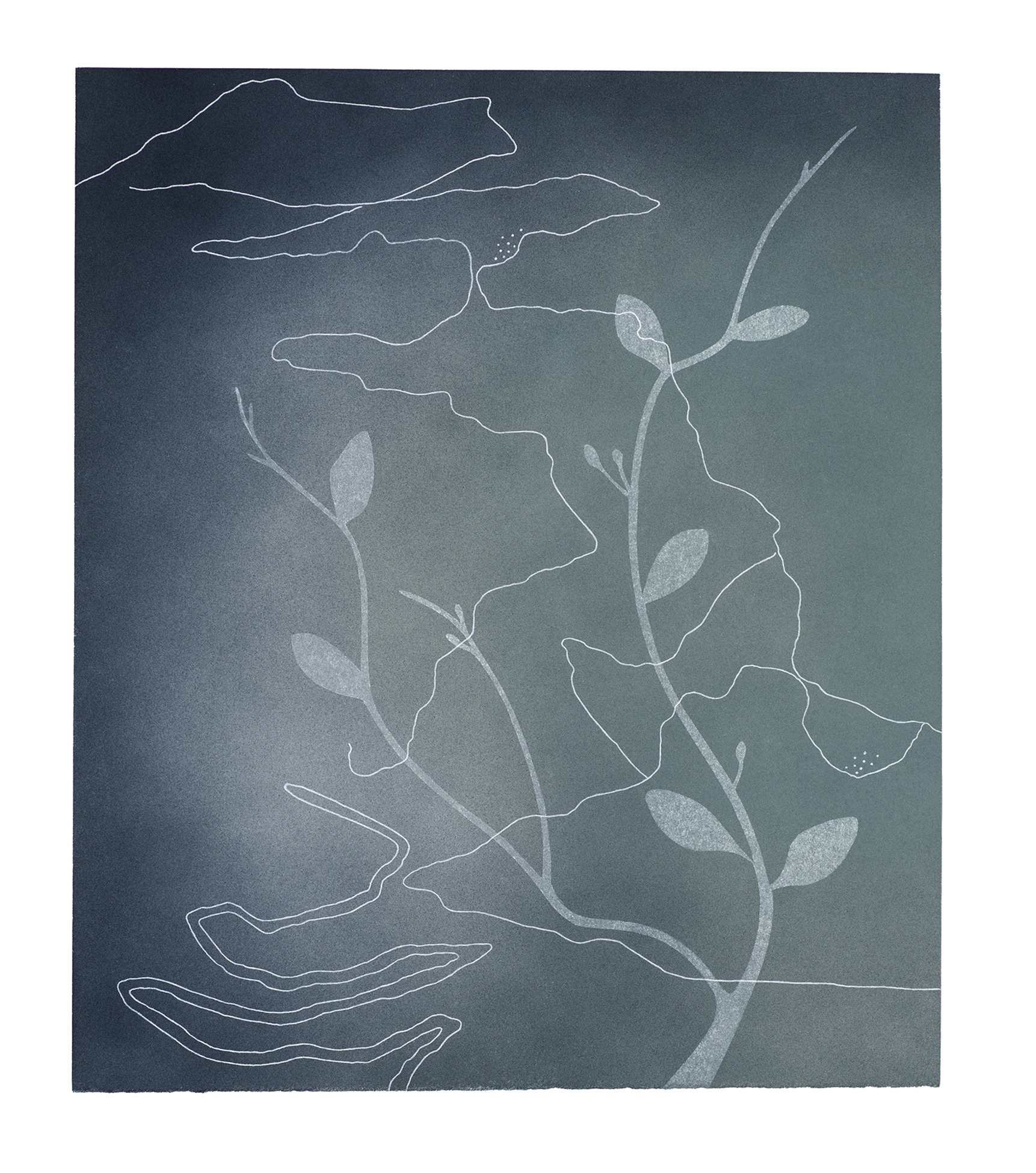

- Desire of returning I, 2021, intaglio collagraph, 76 x 56 cm, edition of 4

- Desire of returning II, 2021, intaglio collagraph, 76cm x 56 cm, edition of 4

- Desire of returning III, 2021, intaglio collagraph, 76 x 56 cm, edition of 4

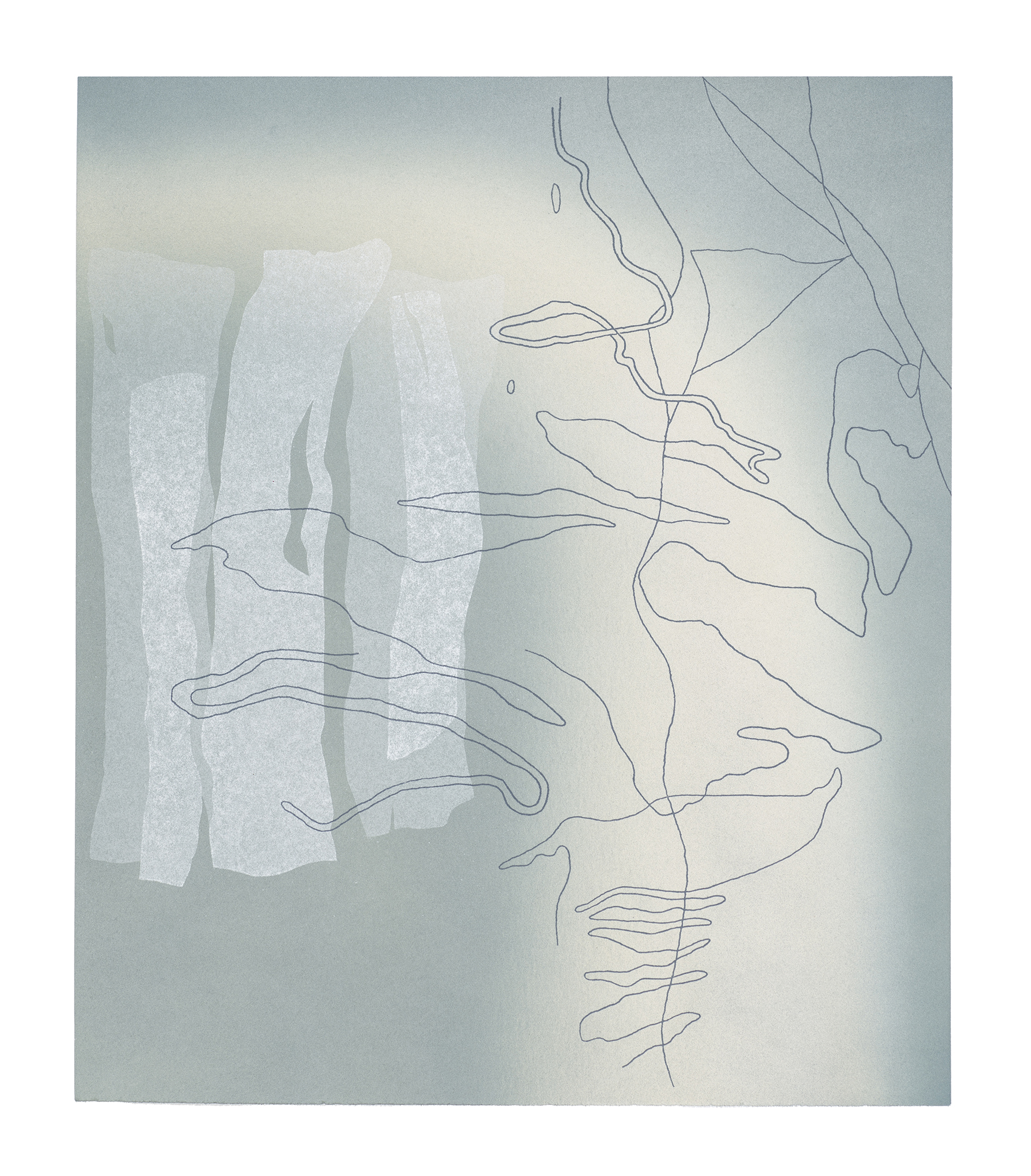

- Lake Whispers #1, 2021, intaglio collagraph and stencil, 45 x 38 cm, edition of 4

- Lake Whispers #2, 2021, intaglio collagraph and stencil, 45 x 38 cm, edition of 4

- Lake Whispers #3, 2021, intaglio collagraph and stencil, 45 x 38 cm, edition of 4

- Lake Whispers #4, 2021, intaglio collagraph and stencil, 45 x 38 cm, edition of 4

The Quiet Place

Melissa Smith’s Without a Sound

Silence is an elusive and faceted condition, often associated with solace or respite. At other times it provokes unease – humans being more inured to noisy distraction than they are to its absence. Even so, true silence is not easily experienced on Earth: bound by uncompromising physics, noiselessness is only possible within a complete vacuum, where sound-waves have no traction.

By the shores of Lake Sorell on Tasmania’s Central Plateau, silence might be apprehended in a manner beyond the usual strictures.

This place is a liquid muse to which Melissa Smith is constantly drawn, personally and as an art-maker. Enveloped by the Lake Sorell environment, a visitor’s sense of peace-and-quiet is contingent, for there is at work a myriad of beats, rustles, rumbles, gurgles and drips, of bird, animal and insect calls, and even the breath of the tiniest breezes, all forming a dense and energetic orchestra.[i] Such sounds serenade us constantly, while others are beyond our hearing: the deep murmurs of tree trunks, or of unseen underwater happenings.[ii]

This all contrasts deeply with the Babel of contemporary urban spaces, where nature’s enduring song is suppressed by a cacophony of human-generated noise, much of it mechanical, stress-inducing and harsh. Even far above our cities, in that luxurious vacuum beyond our atmosphere where, famously and frighteningly “no one can hear you scream”, physicists have detected “vacuum noise”.[iii]

At Lake Sorell, where land meets water, silence might be construed as an absence of both non-natural sound and of the human voice.[iv] Further, we might think of silence more abstractly, not as a physical condition in itself – a state of complete quiet – but as a secular spiritual experience, a receptiveness of the psyche, an inner stillness. The most intimate human sounds – the body’s breath, its heartbeat, its gentle signs of life – might be detected. But, at the epicentre, we might slip into that state embodying the truest of silences: the quieted mind. Melissa Smith’s work invites such a state. Or, perhaps, it induces it: regard the vast offerings contained in Smith’s Hushing (Day) & (Night) [2021] and the gentle Echoes [2021] wherein the simplicity of form propels us towards a desire for stillness.

—

A certain solitude, for the open and willing soul, is easily accessed at a place like Lake Sorell. In Smith’s Lake Whispers [2021], Silent Beacon [2021] and Listen Deeply – Lake Sorell [2021], the sparse imagery deployed – a slender plant-form here, a lozenge of icy light or a translucent cloud-shape there – suggests stillness and a contemplation of the solitary human in communion with the elements. While different forms of solitude can be identified throughout history – solitudes of isolation and fear are both imposed or aroused by those in power – here we see another type of solitude, one which transcends power: “It is a solitude based on the idea of Epictetus that there is a difference between being lonely and being alone. This third solitude is the sense of being one among many, of having an inner life which is more than a reflection of the lives of others. It is the solitude of difference.”[v]

Here, at Lake Sorell, that quality of solitude is not one of anxious apartness, but one where all forms of individual difference and distinction – endlessly identifiable among the various components of the ecology – together form a wave of deep connection.

—

With their gently insistent colouration, layered topography and isographic allusions, Smith’s drypoint prints inhabit a dominion of special tranquillity. They are constructed upon what might be viewed as a small version of a landscape: a cardboard block sealed with shellac. This is like a cross-section of land whose surface is used for imposing a series of delicate yet sturdy grooves and marks. After being submitted to this age-old intaglio process, the block is then inked, wiped and sent through a press. One surface begets another, their geographies in communion.

Smith describes Lake Sorell as a place of serenity subject to the changing moods of weather patterns. The signs of this meteorology are visible across the panoramic views afforded from the shoreline, reflected in the wave-like formations that sweep and layer themselves across Smith’s prints. In the dominant Western understanding, “landscape” is an arrangement of natural components which we “view” as an appraising outsider.[vi] Other approaches, notably those lived within Australian Indigenous cultures, wisely insist we are indivisibly part of Country.[vii] As Christopher Manes observes, it is now time – as we contemplate the environmental ruins around us – to change the tired old conversation in which “man” has been at the centre of conversation in the West, occluding the natural world and leaving it “voiceless and subjectless”.[viii] It is time to put the entire ecology of web-like connections in the foreground.

—

A faint murmur [2021] suggests the stirring of heightened senses when a person intentionally connects with nature, and the art of deep listening is activated as a form of ontological investigation. In this space, we listen with more than our ears: images, scents, tastes and textures provide more information as we quiet our busy, critical minds. In A faint murmur that holism may be detected in the thread-like markings that map out the waves and latitudes of what we might interpret as the softest of sounds. Listening to this, we are not separated from what we hear, but are joined by the intricate mechanisms of the inner ear: on one side the mind, on the other the enormous intelligence and happenings of nature, appearing aurally.

Sound artist Jay-Dea Lopez, whose recordings from the area are projected into the gallery space, brings the inaudible to the forefront of our attention. His specialised recording equipment, describes an “unheard universe” in which “trails of sonic activity” drift around us, where frequencies too low to be discerned groan in the earth beneath our feet, where electric pulses radiate, and where ultrasonic clicks from insects remain unrecognised.[ix] Across the inviting horizon of A faint murmur, all this is implied; we listen with our eyes to what it conjures.

—

In Smith’s suite of works, Desire of Returning [2021], we see individual Welcome Swallows (Hirundo neoxena), which return to the lake every year as a migratory species.[x] For them, “home” is a complex tapestry of environmental conditions, centred on a specific location. We might connect their powerful magnetism towards Lake Sorell as a signifier of our own desires for a sense of wholeness and belonging, located not so much geographically but moreso within our inner life. There, we find a silence and solitude that binds us to the physical world, of which we are a living component, listening and belonging; where we are “human merely being”.[xi]

[i] Sontag, Susan, ‘The Aesthetics of Silence’, in Aspen no. 5 + 6, item 3, 1967, http://www.ubu.com/aspen/aspen5and6/index.html

[ii] See Lopez, Jay-Dea, ‘Raising the inaudible to the surface’, 31 August, 2014, https://soundslikenoise.org/2014/08/31/listening-to-the-inaudible-field-recording-and-the-pursuit-of-the-microsound/

[iii] See ANU ‘Sounds of silence proving a hit’, 24 Aril, 2012, https://physics.anu.edu.au/news_events/?NewID=29

[iv] Sontag, ibid. Sontag contends that “a genuine emptiness, a pure silence” is not feasible conceptually or in fact.

[v] Sennett, Richard, ‘Sexuality and Solitude: Michel Foucault and Richard Sennett’, in London Review of Books, Vol.3 No. 9, 21 May 1981.

[vi] Salazar, Juan Manuel Palerm, ‘On Silence in the Landscape’, https://repozytorium.biblos.pk.edu.pl/redo/resources/33224/file/resourceFiles/PalermSalazarJ_ CiszyKrajobrazie.pdf

[vii] Kankahainen, Nicholas, ‘Refiguring the Silence of Euro- Australian Landscapes’, JASAL: Journal of the Association for the Study of Australian Literature, vol. 15 no.1, 2015. Kankahainen writes of how the “silence” found in many colonial-era descriptions of Australia is based “not so much in an absence of meaning than a failure of Europeans to speak about or make sense of the country and inhabitants they encountered”.

[viii] Manes, Christopher, ‘Nature and Silence’, in Environmental Ethics, Vol. 14, Winter, 1992, p350.

[ix] Lopez, ibid.

[x] Australian Government Department of Sustainability Environment, Water, Population and Communities, Interlaken Lakeside Reserve, Ramsar Site Ecological Character Description, September, 2012, http://environment.gov.au/water/wetlands/publications/interlaken-lakeside-reserve-ramsar-site-ecological-character-description

[xi] See E.E. Cummings’ poem ‘I thank you god for most this amazing day’ (1950)

—

Without a Sound is at Devonport Regional Art Gallery 16 October to 27 November. www.paranapleartscentre.com.au/devonport-regional-gallery/

Melissa Smith is winner of the inaugural WAMA Art Prize with her work Listen Deeply – Lake Sorell (2021). wama.net.au/wama-art-prize-finalists/

—

Join the PCA and become a member. You’ll get the fine-art quarterly print magazine Imprint, free promotion of your exhibitions, discounts on art materials and a range of other exclusive benefits.